VOICES OF RESILIENCE

A Nashville Environmental Justice Initiative Story Archive

A collaboration of the Nashville Environmental Justice Initiative, Urban Green Lab and Tennessee State University are creating a unique archive of oral histories to foster active community listening and address the growing issues brought by a shifting climate.

The archive features the voices of some Nashville community members experiencing climate change first, worst, and longest. Each person shares their story, allowing us to document this moment in Nashville's history in their voice and perspective.

Click the button to view the interactive storymap.

Listen to the Archive

Listener Note: These interviews may contain references to drug use, suicide, domestic violence, and illegal activities.

Hear from Nella “Ms. Pearl” Frierson

Nashvillian in Community Gardening

"I have never experienced this…ever. It’s like there used to be a shield where the sun gets through, but now…you feel like your blood is boiling. We have to be realistic; it’s too hot. The same sun, the same time or year, it’s threatening. [Being outside] it used to be joyful, but now it's... uncomfortable. Most little children do not be outside…ever.”

Climate Connection

As cities continue to grow, so does the intensity of the heat trapped within them. Concrete buildings, asphalt roads, and limited green space contribute to what's known as the urban heat island effect, where urban areas experience higher temperatures than surrounding rural areas.

Urban heat doesn't just make Nashville summers uncomfortable—it can have serious, long-term consequences, particularly for vulnerable populations who are already facing multiple layers of inequality. Many of the city’s most vulnerable residents live in areas close to heavy industry, busy highways, and overdeveloped spaces—places where the heat is often felt more intensely. Without enough green spaces or cooling resources like cooling shelters, and with pollution levels higher in these areas, the health risks are much greater, too. Designing or revitalizing cities with greenspace like Brooklyn Heights Community is the most effective, long-term solution to combating the urban heat island effect.

This is a reality that Ms. Pearl knows all too well. The sweltering heat she describes is a growing struggle in her North Nashville neighborhood, and unfortunately, it’s not an isolated experience. As Nashville continues to expand, the effects of extreme heat on human health, well-being, and the environment are becoming even more urgent. For Nashville's marginalized communities, the rising temperatures aren't just an inconvenience—they're a real public health concern that demands our attention.

Additional Information

Hear from Vicky Batcher

Nashvillian Who has Experienced Homelessness

"I think it's just going to come to a time when we won’t be able to predict the weather anymore. It seems to be colder longer and hotter quicker. You don’t have that week to prepare. Being homeless, you had a week to prepare… We need to be able to prepare…but now…There is no slow progress into the seasons. We don’t have time to prepare. Pretty soon, we’re not going to have a spring or autumn."

Climate Connection

Unhoused Nashvillians like Vicky, who live among the elements, are more attuned than most to the shifting climate. This community experiences these changes first, worst, and longest. Often, we associate climate changes with warmer temperatures but the outcomes of shifting climate are more varied and far-reaching.

Vicky’s experiences indicate a significant departure from climate patterns as we know them in Middle Tennessee. As she correctly predicts, our seasons are evolving into something manifestly new. Our ability to read these dramatic seasonal shifts directly impacts those living outdoors. These rapid pivots in our climate also test our city’s capacity to prepare for more dire consequences.

For folks like Vicky, we have moved away from communities that work in concert with the outdoor world rather than in spite of it. A better Nashville will require a return to a whole environmental approach to our city’s design and development.

Additional Information

Hear from David Wooten & Terri Masterson

Nashvillians in Transitional Housing

"People don't look at [climate change] though. They think of weather, they think of rain and snow. You know, when you say weather, that's what you think of, rain and snow. No, it's really dangerous. I mean, hurricanes have gotten so much worse. Tornadoes have got to where now they don't come in one or two, they come in three or four at a time. No, there wasn't as much flooding back then either. Back then it was unheard of. It just didn't happen near as much as it seems to happen today."

Climate Connection

David and Terri's experiences living in tent encampments in Middle Tennessee highlight the severe challenges of surviving extreme weather, particularly harsher winters among vulnerable populations. With increasingly extreme cold snaps and longer summers, the homeless community faces tough conditions that test their survival skills. For David, who uses a wheelchair, the cold is even more difficult to manage, making it harder for both him and Terri to stay safe and warm. Despite these struggles, David and Terri along with others in the homeless community, demonstrate remarkable resilience, adapting to the harsh conditions with resourcefulness and adaptive strategies.

David and Terri's story shows how people can adapt to changes in the climate across the board, even in industries like construction. With decades of experience as a framer before his disability, David has seen how construction techniques have had to evolve to withstand stronger storms and more extreme weather, such as tornadoes and floods. In response, building codes and methods in Middle Tennessee will have to adapt quickly to meet the need. However, making these changes comes with higher costs for resilient construction materials, the need for a labor force skilled in adaptive building practices, and updates to Nashville codes and permits. All of which local businesses and decision-makers will have to contend with to forge a sustainable solution

Additional Information

Hear from Tom Kunesh

Middle Tennessean Sharing Indigenous Wisdom

Maybe it’s kids that are growing up near creeks and rivers, that'll save us. Parents who bring their kids to creeks and rivers and lakes treasure animals. But the biggest thing is, the change in the number of animals. How people look at animals–we even have less contact where when I grew up, where I grew up, people had constant contact with animals.

Climate Connection

Tom’s story is a meditation on the greater culture of care for the earth, resources, ourselves. Far from a novel idea, indigenous groups have been long touting this simple truth: we are not separate from the natural world—we’re stitched into it. Somewhere along the way, that truth got buried beneath concrete and convenience. We began to think of nature as something "out there"—a destination or a backdrop, rather than the very system that sustains our lungs, our food, our quietest joys. But the forests we clear, the rivers we dam, the species we lose—they are not external tragedies. They are personal losses, whether we choose to feel them or not.

Our reconnection starts with presence, education. When we introduce ourselves, our children to the natural world starting with something as simple as a creek. When we let them watch tadpoles dance in the shallows, we’re doing more than entertaining them—we’re building a future steward. When we grow a garden, or walk slowly through a patch of woods, or even pause to watch the wind moving through trees, we’re letting nature teach us how to slow down, how to listen, how to belong. These simple acts don’t just nourish the earth; they heal something inside us, too.

The climate crisis is not only a crisis of shifting climate—it’s a crisis of relationship. Indigenous cultures across the planet call for a return to our roots. We have forgotten that we’re part of a larger web, and that web is fraying. More than policies and pledges, what’s needed is a cultural shift—a remembering. Indigenous knowledge has long held that the earth is kin, not commodity. Modern science is catching up, but what we need most now is collective humility, and a return to care. Real change will come not just from innovation, but from intimacy—with land, with water, with all living things.

Additional Information

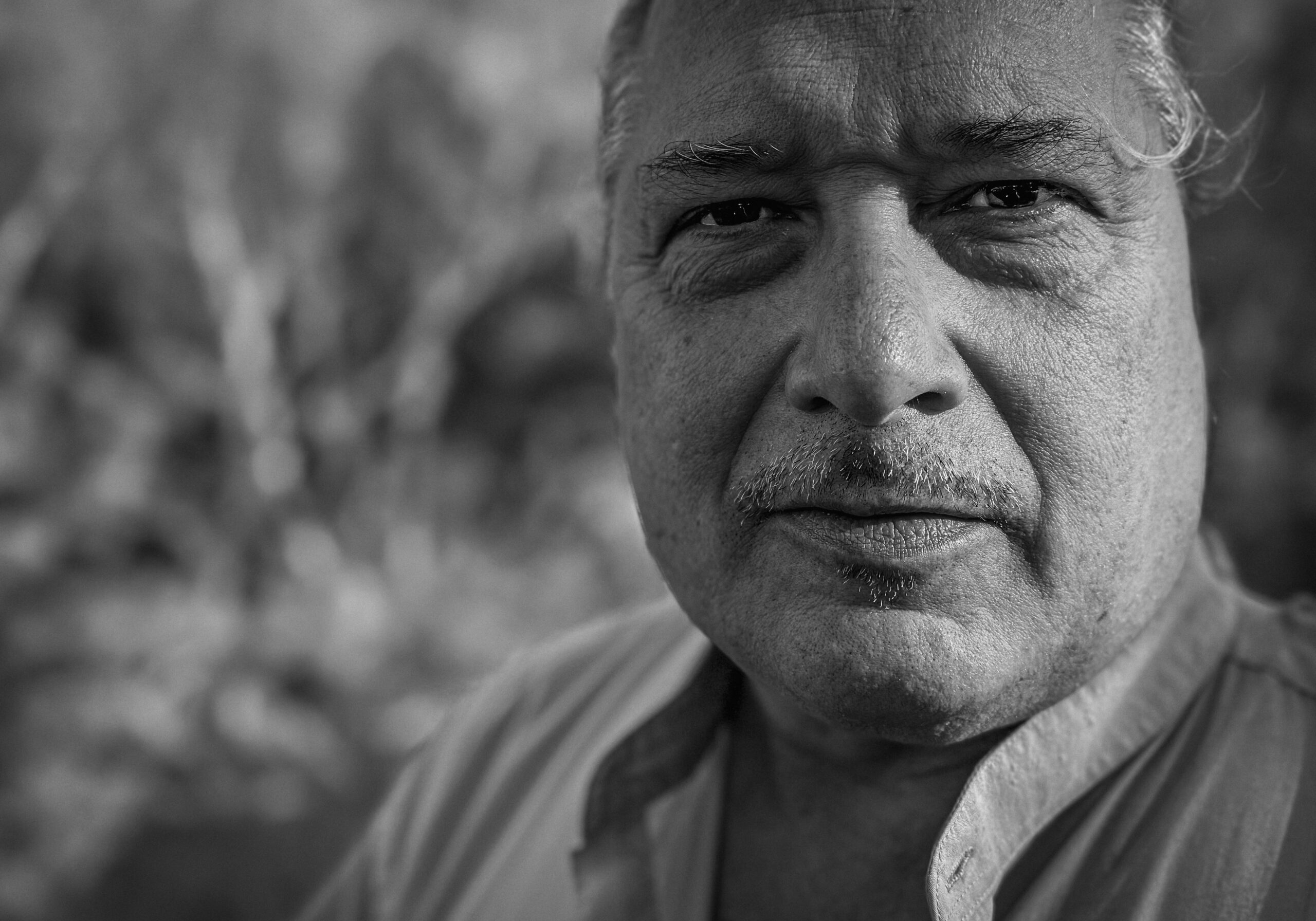

Hear from Gilberto Martinez

Nashvillian Working Outside

"Who said a weed is a weed?

Let things naturally grow. We don’t have to plant new things. Let pollinators do their thing. Starting being ok with letting things grow, letting things be. Let your ecosystem thrive."

Climate Connection

As a landscaper working across Middle Tennessee, Gil has witnessed how the region’s weather has become increasingly unpredictable and extreme. Climate shifts ranging from sudden cold snaps in spring and extended summer droughts are no longer rare occurrences but recurring challenges that directly impact not only the timing of planting but can also affect the health of Gil’s crew due to extremes in heat and cold during installations.

In response, Gil has turned to a climate-smart landscaping approach promoting the use of native plants—species that have evolved alongside the region’s climate and wildlife. He believes this solution will not only improve the survival of the plants he installs, but he knows this will help address the growing challenges extreme weather shifts create for all living organisms within a habitat. These native plants are naturally adapted to local rainfall patterns, soil types, and temperature fluctuations, making them more resilient to both drought and freeze events. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), native landscaping not only requires less irrigation and chemical input, but also supports pollinators and birds, contributing to healthier overall urban ecosystems. Additionally, deeper root systems in native species provide extra ecological services. Native plants can most effectively manage stormwater runoff, reduce erosion, and cool the air—natural solutions to urban environmental challenges.

For Gilberto, landscaping is more than curb appeal—it’s about building biodiverse, resilient ecosystems one yard at a time. In his work, he encourages clients to think beyond aesthetics and toward sustainability: converting traditional lawns into pollinator havens, replacing invasive ornamentals with climate-hardy natives, and incorporating design elements that reduce runoff and heat retention caused by overly concrete areas and urban heat island effect. These small but intentional changes have a cumulative impact, offering a grassroots path to environmental resilience. As cities like Nashville continue to grow and face mounting climate pressures, Gilberto sees native plant landscaping as a practical and hopeful tool for rebalancing the relationship between people, nature, and place.

Additional Information

Hear from Venessa Hammerick & Arthur McQuiston

Nashvillians Living Outside

On preparing for and experiencing more frequent, severe flooding in the encampments:

“When the water gets past them stakes, you better get, because this will all be underwater in a matter of minutes.”

Climate Connection

Flooding events are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change, and for the unhoused or those transitioning to shelter, the consequences can be devastating. Unlike those with stable housing, unhoused individuals often live in areas highly susceptible to flooding—such as underpasses, riverbanks, or abandoned lots—without access to proper shelter or early warning systems. When floods hit, as we heard from Mama V and Arthur, folks can lose everything: their few belongings, access to medical supplies, and even their lives. Emergency services may not always prioritize homeless populations, and relocation to shelters—if available—can be chaotic and dangerous, especially for those already dealing with physical or mental health challenges.

As we hear about the harrowing events of the recent floods from Mama V and Arthur’s perspective, the immediate dangers of living with these

The environmental fallout from flooding compounds these hardships. Standing water can lead to outbreaks of waterborne diseases, mold growth, and increased exposure to toxins, especially in urban areas where runoff includes oil, sewage, and industrial waste. Many unhoused people lack access to clean water and sanitation facilities, putting them at even higher risk of illness in the aftermath. On top of that, support systems like outreach programs, soup kitchens, or mobile clinics are often disrupted or damaged by floods. In this way, the environmental impacts of flooding don’t just affect infrastructure—they also deepen the vulnerability and marginalization of people experiencing homelessness.

Flooding doesn’t just bring immediate danger—it also makes life a whole lot harder for people without stable housing. When sanitation systems break down, you get dirty water everywhere, mold starts to grow, and diseases like hepatitis A or leptospirosis can spread fast. On top of that, the places where unhoused folks usually get support—like food pantries, outreach spots, or mobile health clinics—can get shut down or wiped out by the storm. That means even fewer resources when they’re needed most.

And it’s not just about losing stuff or getting sick—floods can also push people out of the few places they’ve managed to settle, often leading to stricter rules or heavier policing around encampments. Cities trying to clean up after a disaster sometimes end up pushing people further into the margins instead of helping them. So when the waters rise, it’s not just a weather event—it’s another hit in a system that’s already stacked against folks trying to survive without a home.

Additional Information

Hear from Frederick Cawthon

Nashvillian in Sustainable Agribusiness

“This is not normal. And you can layer over and look at the data where greenhouse gas emissions, when they're increasing, and then layer over, okay, when do we start seeing all these tornadoes and everything is just expanded, where the seasons are expanding. And then even if you look at the degree days and how we keep rising, we're getting hotter and hotter. We're doing that.”

Climate Connection

Frederick’s business focuses on the agricultural, medicinal, and industrial applications of hemp. Frederick sees this crop as an intersecting opportunity for commerce and agriculture – the very words on the state seal. He envisions a new type of agribusiness, one that reimagines a system where agriculture and commerce aren’t in conflict, where the scales of earth’s resources, people, and prosperity find equilibrium, and where equity and access are expected. His mother’s cancer trials led Frederick to pose introspective questions about the tension we often feel between natural and human systems. It is a tension of our own making, one that Frederick believes can be relieved through indigenous wisdom, which suggests a return to a more equitable balance between people and planet.

Frederick’s story connects the dots between our impact on the planet, the negative health, environmental, and economic outcomes impacting loved ones, and the perceptible shift towards more sustainable solutions in business and beyond. He’s stumbled on the form of true resiliency, something those who seek true environmental justice strive towards.

Additional Information

Hear from Alex Willoughby

Nashvillian in the Tornado's Path

"We took a direct hit. The neighborhood was just demolished. I mean my neighbor's roof got literally picked up and taken away. We had a couple big trees come down on the house.

It sounded like a thousand trains mixed with maybe like a thousand squealing pigs is what that tornado sounded like. And just, just boom, it just, it came through, unfortunately killed a couple people not far from my house."

Climate Connection

Tennessee is no stranger to powerful storms. Tornadoes and intense straight-line wind events like derechos have long left their mark on the state’s rolling hills and quiet towns. But in recent years, something has changed. These storms are hitting harder, lasting longer, and arriving in seasons and regions that once felt relatively safe. Behind this growing instability is a shifting climate—one that's turning up the volume on extreme weather across the Southeast.

At the heart of these changes is a warming atmosphere. As global temperatures rise, so does the energy available for storm formation. Warmer air holds more moisture, leading to heavier rainfall and more explosive storm development. In Tennessee, where cold fronts from the north often collide with warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico, these juiced-up conditions create the perfect storm—literally. Tornadoes, once more common in the spring and concentrated in “Dixie Alley,” are now appearing in fall and winter, and striking in areas previously thought to be lower risk. Meanwhile, derechos—long, bow-shaped clusters of thunderstorms that can produce widespread wind damage—are gaining strength and frequency, packing hurricane-force gusts that tear through forests, farmland, and neighborhoods in minutes.

The impacts are profound and deeply personal. Homes and schools are ripped apart. Entire towns can be left without power for days or even weeks. Flooding ensues. Farmers lose crops, communities face long and costly recoveries, and the emotional toll on neighborhoods is lasting as Alex still describes the devastation nearly five years after the horrific 2020 tornado that hit East Nashville. These storms not only destroy human communities, but also devastate ecosystems. When forests are leveled and streams are clogged with debris, wildlife loses habitat and water systems are thrown out of balance. And for many Tennesseans, especially in rural or low-income areas as we saw in Waverly, TN in 2021 and the 2024 storms in East Tennessee after Hurricane Helene, recovery isn’t just slow—it’s often incomplete, widening already existing disparities.

What we’re witnessing in Tennessee is part of a larger pattern—climate change doesn’t just mean warmer summers or rising sea levels. It means more chaos in the sky. More nights where the weather radio doesn’t stop. More mornings where the sun rises over broken trees and shuttered homes. And while mitigation at the global level is crucial, adaptation at the local level—through early warning systems, storm-resilient infrastructure, and community preparedness—is equally important.

The storms are telling us something. The question is whether we’re ready to listen—and to act.

Additional Information

Hear from Kate Fields

Native Nashvillian Feeding the Flocks

“Food Justice, it’s essentially when folks are able to have enough culturally appropriate foods, when they {do not} wonder about where their next meal is going to come from. They have access to fresh foods. That we all get to have those things that we need to nourish our bodies in healthy ways.”

Climate Connection

Seasonal changes, extremes in temperature, and more frequent, severe weather events do not only affect day-in-day-out Nashvillian activities. These specific climate shifts directly impact food production. Climate shift consequences include growing predictability in the planting schedule, erratic dips or overflow in rainfall, soil degradation, lower, less nutritious crop yield, and an increase in pests and plant disease. These consequences can trigger secondary consequences that disrupt the local food system altogether. Disruptions to Nashville’s food system reduce local availability, drive higher prices for food with less nutritious value, and create a greater dependence on food produced and processed outside of the local system. Collectively, these effects have been exacerbating issues with food insecurity and healthy food access that plague our city. Food justice in Nashville is a growing concern as the city grapples with issues of food insecurity, inequitable access to healthy food, and the disproportionate impact on marginalized communities.

A recent study by Vanderbilt University Medical Center found a staggering 40% of Tennessee families are food insecure. According to a companion study, Metro Social Services departments, 1 out of 10 Nashvillians are food insecure. This is a blatant irony in a state with a long tradition of agriculture. The Tennessee state seal boasts agriculture and commerce!

The highest concentration of food insecurity is found in North Nashville zipcodes. Many of these neighborhoods, particularly lower-income area and low-access communities (LILAC) face challenges in accessing fresh, nutritious, affordable food. They are historically communities of color and immigrant communities. Food deserts and food swamps are prevalent, where residents may live far from grocery stores or farmers' markets, relying on corner stores or fast food that often lack healthy options. Efforts to address food justice in Nashville focus on returning food sovereignty to neighborhoods and low-income populations. These efforts include community gardens, local food cooperatives, and initiatives by nonprofits that work to provide fresh produce through mobile markets or urban farms. These initiatives aim to not only provide access to healthy food but also empower communities, encourage sustainable practices, and create local food systems that prioritize equity. The city’s movement toward food justice emphasizes the importance of creating inclusive solutions where all Nashvillians can enjoy the benefits of healthy, sustainable, and culturally appropriate food.

Additional Information

Hear from Elois Freeman

Native Nashvillian Who Came Home

"I'm observing this dynamic of what's happening in my community, even to the impact, how it impacts education, how it impacts safety, how it, it just impacts everything. Different people have different streams of support. And so again, we're always looking at how can we help those who are not in the streams of support to know that there is help."

Climate Connection

Climate shifts, including extreme weather, seasonal changes, and urban heat effects, are impacting both our built environment and natural resources. However, the repercussions of environmental injustices and racism equally and profoundly impact our social sphere. No aspect remains untouched, particularly those impacting health, business, housing, education, and family dynamics.

One response to these challenges is fostering resilient communities. These communities are designed to strengthen daily well-being and reduce the impacts of disasters by being proactive, adaptable, and able to recover quickly from disruptions. Resilient communities rely on strong, interconnected relationships where people can quickly mobilize to support each other. Through shared civic responsibility and a well-organized care structure, these communities can overcome environmental, economic, and social challenges, emerging stronger in times of crisis.

Throughout her interview, Elois shares her experience with Nashville’s historical pitfalls and emerging challenges. Yet she also observes all the makings of a successful, resilient community. One where food, homes, clean air and water, health, and, most importantly, people are top priorities. Ever hopeful, Elois points to the wealth of opportunity Nashville has to achieve true resiliency through relationships and connection.

Additional Information

Interactive Storymap

Scroll through the interactive storymap to gain a deeper experience of the stories behind Voices of Resilience.

*Please allow a moment to load.

To visit the full storymap site:

Partner Spotlight

The Nashville Environmental Justice Initiative (NEJI) is a partnership between Urban Green Lab (UGL) and Tennessee State University (TSU). TSU and their Geographic Information Sciences Laboratory (GIS) has historically been a champion for climate and environmental justice.

Since the department's founding in 2000 by Dr. David A. Padgett, GIS has provided technical assistance to environmental justice and community-based organization (CBO) stakeholders in support of a number of community-based participatory research (CBPR) activities, including:

- Applications of EJ SCREEN and ArcGIS Online in support of CBO community air quality monitoring project in the Pleasantville Community in Houston, Texas.

- Stakeholder training in geoscience and cartography in support of strategies to mitigate the negative impacts of landfills upon human health in the Wedgewood Community in Pensacola, Florida.

- Real estate data collection and analysis in support of CBO efforts to develop heritage tourism and preserve critical historical resources in the Africatown Community in Mobile, Alabama.

- Community-based participatory asset mapping and hydrological data analysis in support of community legal actions versus a proposed inland port facility that threatens the quality of life in the historic Turkey Creek community in Gulfport, Mississippi.

- Geographic information systems (GIS) training in support of a community-based flood mitigation program in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward.

To learn more about the Oral History Archive, contact Stephanie Roach at stephanie@urbangreenlab.org.