A guest blog from the Cumberland River Compact.

It all started with a cactus.

My neighbors had one growing in their front yard, which always struck me as weird– this is Tennessee, not Texas! I’d joke to my roommate when we passed by on walks. One day, I felt a little more curious than usual and started googling to find out what species our spiky friend was. Unexpectedly, I stumbled upon a surprising fact: this cactus, the prickly pear, was actually native to Tennessee!

As someone born and raised in Nashville, I’ve always been well aware of the impacts of rapid urbanization on the natural world around me. Growing up, I’d stare out the car window and try to imagine what the landscape in front of my eyes looked like before the apartment complexes, the housing developments, and the mall. I imagined dense forests where green lawns now splay out; craggy limestone cliffs where the highway now carves its way through rock.

But I never imagined cacti - and I never imagined prairies. I’d managed to go my whole life so far without learning the truth: species evidence and written accounts suggest that natural grasslands flourished throughout the greater Nashville area before it was developed by European settlers. These ecosystems played host to plants you’d expect to see in Kansas, maybe, or New Mexico: prairie dropseed, prickly pear, grama grass. Research from the Southeastern Grassland Institute (SGI) reveals three main types of grassland that once blanketed Nashville:

Prairies: These open, treeless landscapes of low-lying plants once covered the Highland Rim west of town. Plants like coreopsis, little bluestem, and goldenrod thrive here.

Limestone glades: Despite great losses, the Nashville area is still home to the worlds’ highest concentration of these unique ecosystems where rock deposits near the soil’s surface prevent the growth of large trees. They host rare wildflowers, lichens, and succulent plants.

Savannas: Like prairies, but sparsely populated with large trees like oaks and elms. These landscapes used to surround limestone glades in the Nashville basin and housed prairie plant species that prefer slightly deeper soil beds than those found in the glades.

The Disappearing Act

Tennessee’s grasslands, like many, were maintained with fire. Centuries ago, natural wildfires and Native American land management practices mitigated forest growth and allowed biodiverse ground cover to flourish– however, once Europeans moved in, they implemented fire control measures and built settlements that caused prairies and savannas to begin to disappear.

An estimated 99% of prairie and savanna ecosystems in the southeastern U.S. have already been lost to overgrowth and development, and what’s left is being destroyed at an alarming rate; in fact, according to SGI, Tennessee lost over 216,000 acres of native grassland just between the years of 2008 and 2016.

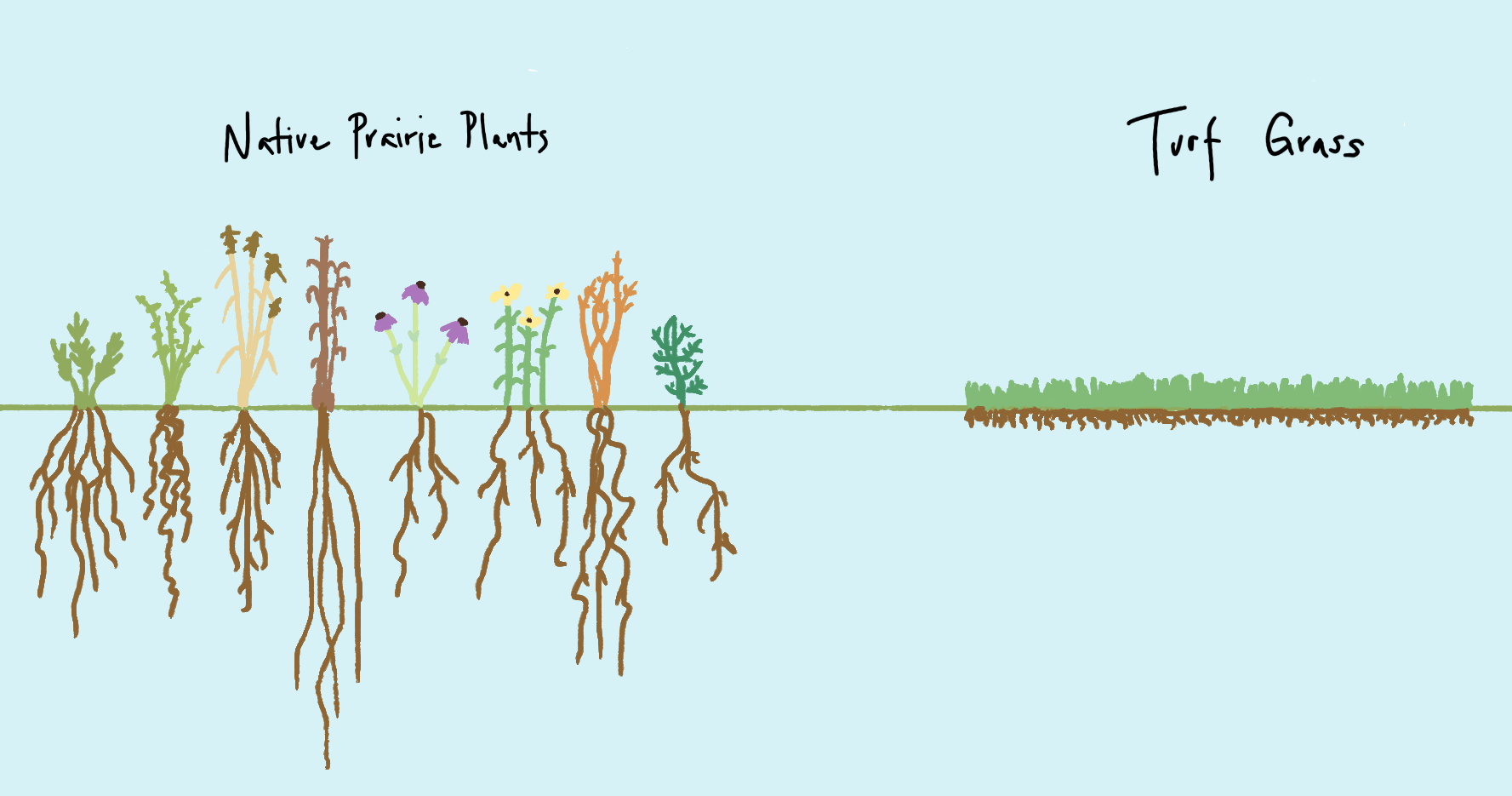

The disappearance of native grasslands is a problem for the plants and wildlife that call them home, but it’s a problem for humans, too. Nashville, as we all know well, is subject to periodic heavy rainfall throughout the year; prairie plants function like a sponge that drinks up that water. Their deep, mature root systems hold soil in place to prevent erosion, and the ground cover they provide acts like a net to trap and slow down runoff.

As prairies disappear, they’re largely being replaced with two things that do NOT manage stormwater well at all: pavement and turf grass lawns. Pavement is an impervious surface: when it rains, water doesn’t seep through it and absorb into the ground. Instead, it has to travel until it reaches a stream or storm drain (and eventually the river). A grass lawn is a pervious surface, meaning it absorbs rainwater - however, its best efforts can only go so far. Turf grass has shallow root systems that are easily overwhelmed by a lot of rain - ever stepped on a soccer field after a storm and found your shoe immersed in a mud puddle?

Runoff is a water quality issue because it gathers pollutants like fertilizers, road salt, pesticides, litter, and animal waste on its way back to our streams and rivers - plus, it contributes to urban flooding, which can damage infrastructure (hello, potholes!), not to mention homes and businesses. When water sinks into prairie landscapes, their deep-rooted plants can absorb pollutants; then, that water gradually flows underground and feeds nearby streams. This “baseflow” is a crucial resource during Nashville’s dry summer months.

A Pocket-Sized Solution

That’s why my coworker, Natalie, is making house calls all over Nashville today to consult with residents about putting Pocket Prairies in their yards. Natalie is the urban waters program manager for the Cumberland River Compact, a nonprofit focused on promoting water health. I just take photos for the Compact, but Natalie is in the field every day advocating for lawn alternatives that improve Nashville’s water quality; today, she’s been kind enough to bring me along to her consultations and tell me about the Pocket Prairie program.

Pocket Prairies, she explains, are native gardens that feature wildflowers and other hardy grassland plants. They’re a bite-sized version of the prairie and savanna ecosystems that used to cover Nashville. The Compact provides funding and guidance to help homeowners, churches, businesses, and schools replace some of their grass with a pocket prairie. We’re even able to depave unused parking lots around Nashville and plant these landscapes where the asphalt used to be.

Examples of Pocket Prairies installed in Compact staff’s backyards.

“We’re able to use grant funding to cover the cost of plants and mulch for anyone in Davidson County, so basically all we have to do is convince people that planting a Pocket Prairie is a good idea,” Natalie explains. “These prairie plants - things like coneflowers, water oats, and black-eyed susans - are hardy perennials, so while they require some maintenance, they’re pretty easy even for inexperienced gardeners. We’re confident that recipients of these conservation landscapes will notice improved rainwater absorption on their property, beautiful blooms in spring, and an increase in fun critters like birds and butterflies visiting their yard.”

Pocket Prairies may be small, but the Cumberland River Compact has big plans for their future in Nashville. “With the community’s support, we can turn a handful of pocket prairies into a sprawling network of prairie ecosystems all over town,” says executive director, Mekayle Houghton. “Our hope is that this disconnected but ultimately large-scale prairie restoration project will be instrumental in preserving sensitive species unique to our region, and over time will significantly improve the health of the Cumberland River and its tributaries.”

Compact staff prepare a Pocket Prairie plot in Clarksville for planting.

Join the Movement

Do you have a piece of property you’d consider planting a Pocket Prairie on? Does your school or business have an outdoor area that could use a makeover? Request a free consultation today - a Compact staff member (like Natalie) will visit your property and talk with you about what kinds of plants might thrive there, as well as what the installation process looks like. If the property you have in mind is currently paved, fill out the Depave site interest form. The Cumberland River Compact is proud to provide Nashvillians with resources to help preserve our natural world and make the city a little bit wilder, one pocket at a time.

Jess Awh is the Communications Coordinator at the Cumberland River Compact, where she creates multimedia content to tell the story of water-centric conservation initiatives in Middle TN. Jess has a bachelor’s degree in music with a focus on ethnomusicology from Columbia University. She was born and raised in Nashville and is deeply committed to environmental advocacy in the city she calls home. In her free time, she enjoys playing guitar and hanging out with her cat, Birthday.